ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi: ʻUaʻu

Scientific Name: Pterodroma sandwichensis

Conservation Status:

Federal Status: Endangered (listed in 1967)

State Status: Endangered

IUCN Red List: Vulnerable

Population Size

In the early 1990s, the statewide Hawaiian Petrel population was estimated at approximately 20,000 individuals, including 4,500 breeding pairs. Long-term population trends of Hawaiian Petrels vary on each island. On Kauai, between 1993 and 2013, radar studies conducted by KESRP and Cooper & Day, revealed that the species suffered a catastrophic population decline of 78% (Raine et al 2017), while Hawaiian Petrels on Mauna Loa appear to be precipitously close to extinction. Brightly, however, recent radar surveys by KESRP show that the population decline on Kauaʻi is slowing down. This slowing overlaps in time with increased predator control in the largest known mountain colonies (although a causal relationship cannot be determined as of yet). Numbers of birds at Haleakalā National Park on Maui have potentially increased over the last 20 years, corresponding with predator control efforts and habitat management in the park. Maintaining accurate information about these population trends is critical to guiding what management actions to implement, and whether these management actions are ultimately effective. Updating this information is therefore a high research priority.

Distribution

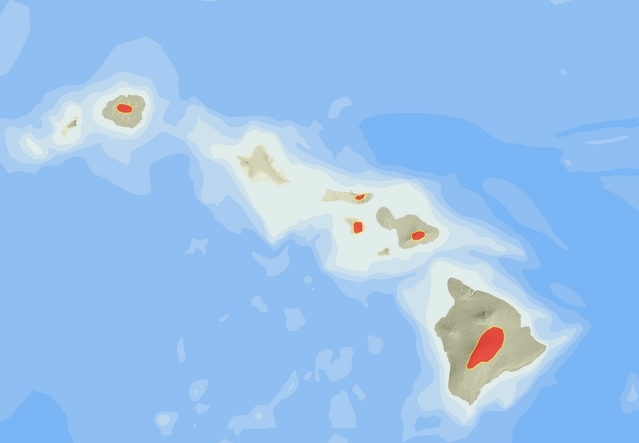

Hawaiian Petrels are found exclusively on the main Hawaiian Islands and were once abundant and widely distributed across Hawaiʻi. Hawaiian Petrel bones have been found in vast numbers at numerous archaeological sites throughout the Hawaiian Islands, including locations like the Ewa Plain on Oʻahu (which is now a suburb of Honolulu) and Mākaʻuwahi Cave in Kauaʻi. As is the case with other seabirds, the combination of introduced predators (such as cats, mongoose, rats and pigs), habitat loss, and human disturbance have dramatically reduced the population and range of these birds. Due to the various threats that face this species, the main populations on Kauaʻi are now concentrated in the north-west of the island in areas such as Upper Limahuli Preserve and Hono O Nā Pali Natural Area Reserve.

Currently, Hawaiian Petrels are restricted to breeding on high elevations of five islands: Hawaiʻi, Maui, Kauaʻi, Lanaʻi, and Molokaʻi. On Hawaiʻi Island and Maui, birds nest on high elevation volcanic slopes in crevices of the open lava fields. On Kauaʻi, Lanaʻi, and in West Maui, colonies occur on steep, densely vegetated slopes in native ‘ōhi‘a forest with ʻuluhe fern understory, and burrows are dug in soil.

Breeding

The Hawaiian Petrel flies to and from its burrow only at night. It is thought that they start visiting their breeding colonies at three years of age, but do not begin breeding until they are at least five or six years old. Interestingly, and for unknown reasons, Hawaiian Petrels in Maui arrive at their colonies in late February, whereas those on Hawaiʻi, Kauaʻi and Lanaʻi arrive up to a month later. After a period of burrow maintenance and social activity, they return to sea for approximately one month – which is known as the pre-laying exodus. Upon their return, egg-laying commences.

Over the next two months, both adults take turns incubating. Once hatched, parents briefly brood the chick before beginning a regimen of extended marine foraging trips to gather food. At this point, both adults are absent from the nest except for periodic visits to deliver regurgitated squid and fish to the chick. Chicks fledge between late September and late November on Maui, and from October to December at the other colonies. Although adults occasionally remain at the colony after fledglings depart, colonies are generally empty by the end of November or early December.

Diet and Foraging

The Hawaiian Petrel forages in mixed-species flocks of birds over schools of predatory fish, such as tuna. Tuna and other large predators, including mahi mahi, porpoises, dolphins and whales drive smaller prey such as squid, fish, and crustaceans close to the surface of the ocean where the petrels can then seize them. Unlike shearwaters, they do not dive to feed. Due to their reliance on predatory fish such as tuna they are sometimes referred to as “tuna birds”.

A recent study conducted by the U.S. Geological Survey found that adult birds fly over 6,000 miles in one trip to collect food for their growing chick!

Identification

The Hawaiian Petrel is the only petrel found in nearshore environments around the Hawaiian Islands, with all other species predominantly found far offshore. It can be separated from superficially similar shearwater species by the white over the top of the bill and the prominent black bar on the underside of the wing. The flight style is quite different from shearwaters in that Hawaiian Petrels fly much faster, and arc above the ocean in much higher and smoother arcs with fewer flaps.

Other species of Pterodroma petrels either have have a distinct dark ‘M’ pattern on the back, have white collars, different amounts of black on the underwing, or gray bellies.